Oughterany Vol. II No. 1

- Oughterany

- Journal of the Donadea Local History Group

- Vol. II No. 1 1999

- Editors - Seamus Cullen, Hermann Geissel, Des O’Leary

- ©The Editors and Contributors

- Layout and Design The Editors

General information about Oughterany

Contents

Selected chapters are reproduced on this page. Click headings to read.

Please not that this web page does not contain endnotes and references

| Editorial | Editors | 4 |

| Noel Reid – An Appreciation | Des O’Leary | 5 |

| Ballinafagh Parish | Noel Reid | 6 |

| Ballinafagh Graveyard | Seamus Cullen and Des O’Leary | 18 |

| Mesolithic Hunters and Medieval Folk in Clane | Niall Brady | 21 |

| Via Magna in Ballagh | Hermann Geissel | 23 |

| Donadea Forest Park | Richard Aylmer | 41 |

| Hortland | Des O’Leary | 56 |

| Hortland Graveyard | Des O’Leary and Seamus Cullen | 66 |

| The Baltracey Quakers | Seamus Cullen | 70 |

| Poverty and Destitution in Kilcock during the 1880s | Karina Holton | 79 |

| A Druid Relic on Cappagh Hill | Karina Holton | 85 |

| A Possible causeway at Knockanally Crannog | Seamus Cullen | 86 |

| Early Christian Burial at Carrigeens | Hermann Geissel | 87 |

| Royal Dun at Duncreevan | Kevin Lynch | 88 |

| In Search of Moss's Road | Martin Kelly | 89 |

| In Memory of a Colleague | Sean Lynch | 93 |

| Possible Henge Monument at Boherhole Cross | Thaddeus Breen | 94 |

| An Aerial Perspective of Oughterany | Noel Murphy and Karina Holton | 97 |

| Clane Millenium Project | Tony McEvoy | 107 |

| Rededication of Aylmers of Painstown Stone Tablet | Richard Aylmer | 108 |

| Bicentennial events in North Kildare | Editors | 109 |

Editorial

It was with great sadness that we learned of the death of our President and Editor, Noel Reid, on 24 December 1997. His initiative was instrumental in starting the Donadea Local History Group and Oughterany Journal, and we are proud to be able to include a posthumous article by him.

We, the present editors, have decided to start a new volume with the present issue. Apart from the format, there will be no major changes, but we intend to broaden the scope of the journal somewhat by placing more emphasis on areas like archaeology, historical geography and related fields. Particularly in this issue we have included an article by Dr Noel Murphy on aerial photography, a research method open to all who are interested in practical landscape studies.

We invite contributions from the general north Kildare areas for inclusion in future publications, though we are aware that too tight a geographical restriction is not always possible. Like the article on the Maynooth – Edenderry Railway in Vol. I, No.2, the present article by Hermann Geissel on the Via Magna extends into neighbouring territories. A linear structure is by its very nature not as localised as other monuments, and it seemed illogical to study the Great Road in Kildare without covering its extent in County Dublin, especially with the St Mochua link to Clondalkin.

We like to take this opportunity to thank some people who have given us their continued help and support over the years. Particularly, we would like to mention Michael Kavanagh of Kildare County Library, Pat Sherry who has always provided us with drawings and illustration (including the cover picture of this issue) and Tracy O’Leary for her untiring typing work. We are delighted that John Larkin and Owen Denenny have taken the task of organising the launch out of our hands.

Seamus Cullen

Hermann Geissel

Des O’Leary

Via Magna in Ballagh

The Slighe Mór in Dublin and North Kildare

Hermann Geissel

Introduction

The most fascinating of all ancient roadways must no doubt be the Esker Riada, the great east-west axis that traverses Ireland from Dublin to Galway Bay and has played such a great part in Irish History, Legend and Mythology. Not only was it the road on which roving poets, saints and armies travelled; it was the arena in which Finn MacCool and the one-eyed Aed (alias Gonn) fought out their battles, moving in a constant see-saw like fashion east and west according to which of the two happened to be favoured by fortune, destiny or superior wit. They were, of course, the sun gods of the East and West, respectively, symbolising in their fight the constant struggle between the rising and the setting sun. The need to portray them as human in Irish legend arose from the pressure on the Celtic storytellers in early Christian times to present their traditional mythology as historic fact and former gods as their mortal ancestors, in order to avoid conflict with the high priests of the new religion.

The Esker Riada is also known as the Slighe Mór, one of the five great prehistoric roads supposedly converging on Tara. It is referred to in medieval Latin texts as Via Magna, a synonymous term also denoting the Great Road. It is therefore somewhat surprising that this roadway also marked a division between the northern and the southern halves of this island, Leth Chuinn and Leth Moga, a dichotomy which, during the second and third centuries ad, prevailed over the traditional division into four (or sometimes five) provinces.

One of the problems arising here is the exact location or course of the Slighe Mór. It is well known that, in general terms, it followed the modern road system from Dublin to Galway (N4/N6), but this is very vague and in part incorrect. Uncertainty prevails in many places, and some documented stretches are mutually exclusive. Which is hardly surprising since we are not looking at a continuous gravel ridge extending from Dublin to Galway, but rather a system of more or less interconnected eskers running in a general east-west orientation, with several parallel ridges allowing a choice in places, and intervening stretches of low ground, even bogland, in other areas.

The present article is an attempt to track this ancient roadway through North Kildare, with a look over the fence into neighbouring Dublin and just a furtive glance into Meath and Offaly. The route in question was identified in a 1940 paper by Colm O’Lochlainn as part of the Esker Riada / Slighe Mór system which was said to have extended from Dublin to Clonmacnoise, and further on to Galway.

Method

The roadway was traced from Dublin through North Kildare to Monasteroris (Edenderry), with the emphasis on the Iron Age / early Christian periods. The investigation focused on historical information, topography and cartography, without undue emphasis on the question whether actual manmade roads were in existence or whether the terrain just offered itself as suitable for traffic on foot or on horseback. Of major interest were in this regard eskers and other stretches of well-drained high ground, suitable river crossings and manmade trackways through the bog (toghers and bog roads).

In this article, the term roadway is generally used in preference to road, though for stylistic reasons this rule is not always strictly adhered to. A manmade road may or may not have existed in a particular location in late prehistoric or early Christian times. Alfred P. Smyth, in his book, Celtic Leinster, points out that the important places to look out for are bottlenecks where traffic is forced through a narrow passage: a ford, a narrow esker in marshy country, a togher, a pass through dense forest – in a generally open, un-enclosed countryside, the traveller is not bound to adhere to a clearly defined route. Still, O Loughlainn argues that there were manmade roads in existence, probably built during the reign of Cormac MacAirt, 3rd century ad, and this is broadly supported by Fergus Kelly who places a period of major road construction around 300 ad.

It is an underlying assumption of this paper that where a known evolved road rides an ideal stretch of high ground between identified destinations (settlements, fords or passes), that it marks an older, possibly prehistoric, roadway.

It is also assumed that roads which have in modern times given way to alternative routings may have left traces on maps as well as in the landscape. Of particular interest here are old field boundaries, especially those with discontinuities, as though taking a ‘leap’ from one roadside to the other. Also, a sudden sharp turn in a road often indicates a deviation from the original route.

Where an ancient roadway is described in relation to its proximity to an existing or documented road, or a Spot Height (‘Spt’) marked on the OS 1:50 000 Discovery Series map, it is done without claim that the exact position of the roadway was fully congruent with the reference feature.

Apart from topographic characteristics and maps both historic and modern, documentary sources, placenames and folklore have been looked at.

All grid references relate to 1:50 000 Discovery Series maps, even where another map is being discussed or referred to. For the general reader, maps of this series (Sheets 49 and 50) are sufficiently accurate to follow the proposed roadways as outlined in the article.

North and South

There seems to be little doubt in the minds of most writers on the subject that the Great Roadway ran from Dublin to Lucan. O Lochlainn’s research has led him to conclude that beyond Lucan the ancient road went along a route via Celbridge, Taghadoe, Timahoe and Monasteroris (NW of Edenderry); he then names a few more stopovers further west, including a crossing of the Shannon at Clonmacnoise, with the roadway ending at Clarinbridge on Galway Bay. Unfortunately, he does not give a clear record of the evidence that led him to this conclusion, though he does mention that St Patrick joined the Slighe Mór at Dunmurraghill, the latter referred to in the Book of Armagh (quoted by the Reverend Comerford) as situated on the 'Via Magna in valle'. Yet O Loughlainn also points out that, according to the Book of Leinster, the Esker Riada passed through Clonard and crossed the Shannon at Athlone. So could there have been a northern and a southern route?

While at the time of Conn of the Hundred Battles, the putative road builder (or discoverer?), the country may have been fairly pacified and united under his powerful high-kingship, there was a definite border between Meath and Leinster in early Christian times (along the Liffey – Ryewater system), with hostile tribes living on either side. Would they each have had their own road?

And what is the meaning of the phrase, in valle? Literally translated, it means in the valley, suggesting that this was the low road and hinting at an alternative high road – perhaps further north, in Meath. It is of course quite possible that valle is merely a corruption of the Irish bealach, as St Patrick must indeed have passed through Ballagh prior to arriving at Dunmurraghill! Either way, the qualifier hints at another via magna.

I shall now sketch out a likely northern route and then take a closer look at the southern route.

The Northern Route

The Esker Riada is generally believed to start in Dublin’s High Street / Cornmarket area. High Street near Christ Church Cathedral is the highest spot in the area, with the terrain falling off towards the Liffey (N - for north), St Patrick’s Cathedral (S), Dame Street (E) and to a lesser degree Thomas Street (W). It is not difficult to trail the ridge down Thomas Street and James Street to Kilmainham, but somewhat harder for the casual investigator to follow when arriving at the gates of the IR railway depot on a Sunday morning. It is therefore better to go back to Islandbridge and take a parallel route driving west on the N4, then taking the first turn left into Ballyfermot. The height of the ridge is visible to the left, but soon the modern road joins it at the Ballyfermot roundabout.

While it is unlikely that the planners of the Ballyfermot street system paid much heed to ancient esker roads, the modern road nonetheless follows the old road west (and the presumed ancient roadway) fairly faithfully up to Cherry Orchard Hospital. However, from here to Ronanstown, the present road system in no way resembles the older roads of only a generation ago, and we have to find our way by taking a left at the tee-junction, followed by a right turn. From Ronanstown – if we don’t miss the old road into Lucan for the maze of new housing estates, roundabouts and cul-de-sacs – we are privileged to enjoy one of the finest esker roads in the country. The ridge is extremely well defined, too perfectly shaped to be totally natural in its present form and now barely more than the width of the road, running at rooftop level. Lucan has always been well aware of its esker heritage, with placenames old and new a constant reminder. But the spectacular Esker Road apart, there is good high ground all the way from Cherry Orchard to Lucan.

Accepting the route so far, it is necessary to cross the Liffey. The most likely ford was at the rapids just upstream of the bridge at Leixlip, with the high ground near the Spa Hotel and golf course providing the link from the eskers at Lucan. This rocky outcrop is very near the present bridge and probably identified a suitable settlement site for the Norse founders of the town.

The rising road from Leixlip – Captain’s Hill – took over from an earlier road between 010 360 and 012 372, now only a footpath leading up the valley of a small (nameless) stream from the fire station. Once on the high ground (beyond modern housing estates, Canal and football pitch), the roadway would have turned west and followed the modern road to the rear (east) gate of Carton Estate, passing right through the Carton grounds and continuing north of the Ryewater to 899 396 just east of Kilcock. (It is obvious that the old roadway would follow the high ground where the present road is too near the river, as at 936 394.)

A system of ridges and remnants of trackways recognisable on the Discovery Series map provide a likely link with the high ground of Ardrums, Spt113, 818 442, and Rathcore, but an investigation of this route into Clonard is outside the scope of this inquiry. Or did the roadway cross the Ryewater into Kilcock? This possibility will be explored below.

Noble and Keenan 1752 (left) shows the road up the hill starting east (downriver) of the bridge at Leixlip; Taylor1783 (right) shows the new road and parts of the old one.

We also need to consider another possibility. If there was indeed a northern and a southern route then the northern route would not have passed through Lucan or started at Leixlip. It would have started in north Dublin probably even at Howth following Howth Road to Fairview, Fairview Strand, Ballybough Road, Summerhill Parade, Parnell Street and across Capel Street. Leaving the high ground at Summerhill Parade the roadway was obviously descending towards the Liffey ford.

Church street Bridge is the oldest bridge in town and there is always good reason to assume that the oldest bridge was built near a pre-existing river crossing a ford thereby facilitating existing approach roads. The exact location of the Ath Clíath, the Ford Of The Hurdles has yet to be determined, but I would go along with Dr Kearns that it was just upriver from Church Street Bridge. I now like to present some cartographic evidence to support this hypothesis together with an attempt to pinpoint its exact location.

Four evolved roads from the North Side converge on a roughly rectangular area enclosed by Blackhall Place, North King Street, Capel Street and the River: Parnell Street (from Howth), Dorset / Bolton Street (from Drogheda), Phibsborough Road / Upper Church Street and Manor Street / Stoneybatter. All four roads get lost in a street system which was laid out with almost complete disregard to older evolved roads. To find the ford, their point of convergence has to be extrapolated. A good fit is halfway between Queens Street Bridge and Church Street Bridge at the point where Lincoln Street meets the Quays. Making allowance for the fact that the Liffey was much wider then especially on the less steeply rising north bank the ford would have stretched out a distance past the present quay walls. I suggest that it extended to the point where Bow Street, whose curved part is the only remaining length of evolved road left in our quadrangle, meets Lincoln Lane, and that Lincoln Lane is in fact built upon the northern part of the early ford or a causeway leading to it. It is worth noting that Lincoln Lane runs level on low ground but Bow Street rises quickly onto high ground.

Lower Church Street is not a part of the old road system; it was diverted from Upper Church Street to meet the bridge. Applying the same line of reasoning to Bridge Street, we extend Upper Bridge Street until it intersects an imaginary extension of Lincoln Lane across the river, just south of Ushers Quay. The intersection point is consistent with the theory proposed above.

Lincoln Lane – the site of Dublin’s ancient Ford of the Hurdles?

The ford it said to have been constructed on the orders of the Ulster Poet, Aithirne the Importunate, who pressed the lesser kings into paying tributes of cattle, sheep and even women to his Ulster king. After crossing the Liffey from the Leinster side, the booty was then driven to the Hill of Howth (Benn Étair). (For an interesting Clane connection, see The Shady Roads to Clane, by H. Geissel and R. Horgan.) Aithirne is said to have lived in the 1st century ad, and, if this account is reliable, then we have good evidence for the antiquity of those roads.

We now follow Stoneybatter and Manor Street to Stoneybatter village. A plaque on the old village green claims that the ancient Road from Tara to Glendalough passed through here, coming down Prussia Street. This may be so, even though O Loughlainn does not show it on his map. However, we are here interested in the other route, up Aughrim Street. It leads onto Blackhorse Avenue and from there to Castleknock, Luttrellstown, staying north of the Liffey and joining up with the road described above at 012 372, north of Leixlip.

St Mochua’s Road?

For us the southern route is of greater local concern as it passes through several baronies of north Kildare. And even if it is not the Great Road, it is of interest for its association with one of our local saints, St Mochua. St Mochua is the reputed founder and first abbot of the monastery of Clondalkin and also has strong links with Celbridge. Furthermore, the ecclesiastical site of Balraheen was dedicated to him, and Timahoe (Teach Mochua) is believed to have been named after him. It is easy enough to link Clondalkin to Timahoe by modern road, and local researchers have been tempted to call it 'St Mochua’s Road'.

Reputedly flourishing in the 6th century ad, St Mochua might have been a contemporary and acquaintance of St Kevin of Glendalough. It is known that Kevin did not set out to found a monastery but rather went to the secluded Valley-Of-The-Two-Lakes to live there as a hermit. Then when word got out that a holy man lived there, others came to join him, and a monastic community began to grow. It was therefore quite conceivable that something similar happened to St Mochua; that he went to live his lonesome life at Clondalkin when he found himself surrounded by a group of followers, went west to Celbridge, where the process repeated itself, then to Taghadoe, Balraheen and so forth until he finally ended up in Timahoe.

Unfortunately, there are certain problems with this line of argument. St Mochua (whose name originally was Cronan Mac Lugdach, the patronymic later corrupted to Mo-chua.) is said to have been Abbot and probably also Bishop of Clondalkin, which does not harmonise well with a hermit on the run. Celbridge is all right. Taghadoe, however, is named for another saint, Ultan ("the Ulsterman") Tua, strongly linked to Clane and at one time sharing its abbot with the Clane monastery. The founder of Balraheen is not known, but its links with St Mochua are documented.

Before we go on to Timahoe, we pass two more ancient monastic sites en route, neither connected with Mochua. The first is Clonshanbo, associated with St Garbhan, brother of St Kevin of Glendalough, and with St German. The other is Dunmurraghill, linked to St Patrick, who is said to have founded there a domus martyrum or martyr house; also in the area is a holy well dedicated to St Peter. Neither does St Mochua appear to be the founder of Timahoe nor is there any record or tradition that he died there. The name, Tigh Mochua, is the only link. We may therefore conclude that while St Mochua certainly was associated with that road and would have used it in his travels, we cannot go so far as to hold him responsible or give him credit for its existence. Nor is it likely that the road was built during his lifetime. It must have been there before him.

Dublin to Celbridge

So what course did the southern route take? O Lochlainn says that it went to Celbridge via Lucan. Judging by the topography, it is quite possible, even likely, that a direct roadway from Lucan to Celbridge existed in early Christian (or pre-Christian) times; but in light of the St Mochua connection I shall propose an alternative. I shall propose that the roadway went from Dublin to Celbridge via Clondalkin. Clondalkin was located on the Slighe Dhála Meic Umhóir (alias Belach Muighe Dála). According to O Lochlainn, this major prehistoric road proceeded from Dublin through Drimnagh, Clondalkin, Newcastle, Oughterard, Naas, Newbridge and Kildare into Munster.

OS 1837 still shows field (and townland) boundaries where the old approach road to the Celbridge ford used to be.

Going back to Kilmainham (see above) we follow Tyrconnell Road to Drimnagh, turn right onto the Old Naas Road, then via Robinhood Road (now interrupted by the Long Mile Road but continuing on the other side) back onto the modern Carriageway, across the Red Cow roundabout and along Monastery Road into Clondalkin, then out on the Newcastle road to Milltown. The roads so far follow high ground all along, are irregular in shape and likely to represent a series of very early roadways.

At 010 305 an elevated ridge runs NW towards Peamount and thereafter two interrupted stretches (broken by the Grand Canal) of small, narrow roads are extant, leading to the railway crossing at 996 314. From here the roadway continued to the west side of the modern Hazelhatch road where soil conditions are more favourable. Field boundaries on the OS 6" map show the way to the ford. According to Tony Doohan, author of A History of Celbridge, there were two fords in Celbridge, one at the Castletown gate and one just upstream of the bridge. The latter is the more likely one for our road; it is in fact directly in line with "Tea Lane", the road leading past the old graveyard with St Mochua's Church, 968 330, and therefore a perfect fit with a known landmark on our proposed roadway. Apart from his accurate description of the ford’s location, Tony says that stone slabs can be seen jutting into the river and stepping stones right across the river, at low water.

Celbridge to Timahoe

From Celbridge the unclassified road continues on high ground, first straight along a modern (corrected) course and then in a winding pattern to Taghadoe Cross Roads. Alexander Taylor’s 1783 map shows no cross roads here, but a strange detour which I am unable to explain. It appears to be a mistake, for Noble & Keenan 1752 does show a cross roads.

Generally the terrain from here on looks less than ideal for an ancient roadway, though there are intermittent stretches of raised ground with good drainage, merging gradually into poorly drained low-lying areas. On the other hand, a manmade road with a metalled surface and drainage ditches must have been viable. Besides, the route is dotted with early Christian settlements, so we have to accept the obvious as evidence.

Following the present road west from Taghadoe we pass Ladychapel cross roads. Here the first Edition Ordnance Survey map (OS 1837) shows field fences that indicate that the old road ran south of the present one, on the high ground. It deviates from the present road at 909 347 and later crosses it at 896 342. From there a raised trackway can be recognised on the ground. The graveyard of Ladychapel does not represent an early monastic or ecclesiastic site. Much of the road between Taghadoe and Donadea has been re-aligned in the last century, and the routes of the old 17th/18th century roads have been described by Seamus Cullen in an earlier issue of Oughterany. But that is not what we are looking for. Here we are interested in the roadway as it might have run a thousand years earlier.

A possible approach to the oval enclosure of Clonshanbo from the east. The only extant roadways are in the bottom right of the picture (parallel to the Baltracey River) and in the centre left, leading away towards Donadea.

We follow the road past Baltracey Cross and on to Clonshanbo. The old roadway can be recognised, partly on the ground, partly from features on the OS 6" map, like sudden bends in modern roads, or field fences that seem to "leap" by the width of a (possible former) roadway. Topographically the stretch between the last esker bumps NW of Baltracey Cross and Clonshanbo is most unsuitable, being low-lying and subject to severe waterlogging, and there is no ready detour; therefore we must postulate an artificial trackway if we insist on including the Clonshanbo site in our itinerary.

From the early Christian site of Clonshanbo, easily recognisable on the OS 6" map as an oval enclosure with its long axis running N-S, a road past the derelict graveyard points directly at Donadea and further on to Dunmurraghill. This is the only high ground leading away from Clonshanbo. Only a short spur of this road is still extant, but there is also a little lane in Donadea Demesne pointing back in the direction, and a field boundary on the OS 1837 map linking the two, thus providing good evidence that the road went this way and on to Dunmurraghill.

Going south from Dunmurraghill we follow a field fence on the OS 6" map to the road east of Staplestown. The straight road through the village is recent. OS 1837 shows remnants of a road bypassing the village at Staplestown Bridge 824 318 to the south and joining up again further west at 815 315. From there it continues to Timahoe, though the ancient roadway would have kept to the high ground north of the modern road between 813 315 and Hodgestown Hill, Spt 116, 791 312; then over Spt 102 to link up with the existing road at Timahoe graveyard 775 321. The extant road between the graveyard and the modern road to Donadea / Dunfierth (Mucklon) is the only stretch of the old road left. It now ends in a tee junction, (772 322), but OS 1837 shows that it once continued straight into the bog.

Hodgestown Hill to Timahoe

Across the Bog

Several toghers – wooden trackways through the bog – have been revealed during turf-cutting operations in the last few decades. Site 17 on the Sights and Monuments Record map, Kildare, Sheet 9 (SMR 9/17), shows a perfect fit between the dry ground at Derrylea 764 332 and the end of an existing cul-de-sac at 745 345 in Drehid townland.

SMR 9/18 shows a togher running from a slight bend in the modern road at 754 327 in a WSW direction to Kilkeaskin 727 319. Ted Craven of Coolearagh, who was then working for Bord na Móna, tells me that this togher was exposed during the early sixties and was found to be at a depth of 4-5’ (1.2-1.5m) from the surface. Going by a rule of thumb of 1m growth per 1 000 years, that would place its time of construction into early Christian times. It appears to aim at Ballybrack, via Dillon’s Bridge and Kilpatrick Cemetery, from where there existed a 'Bog Road' system, known as The Danes' Road, leading through the bog islands of Derrybrennan and Lullymore to Rathangan. Alternatively, it could have aimed at Ticknevin, from where an older togher led to Derrybrennan. Professor Etienne Rynne, who did the excavations there, tentatively accepts a previous dating of The Danes' Road to be contemporary with St Patrick. He concludes that the togher, because of its greater depth below the bog surface, would have to be of an even earlier date.

A third togher (SMR 9/19) has been found and recorded. It ran between Timahoe West 320 755 and Loughnacush 734 328. Since Ted Craven had no recollection of this togher being discovered during his time, I assumed it to have been at a higher stratum and therefore of a more recent date than SMR 9/18. In the event, it was excavated by Professor Rynne in 1966 and was later tree-ring dated by Martin Munro of QUB to 1 485 bc, placing it into the Bronze Age! This togher aims at 719 333, from where the roadway followed the present road to 709 332 and continued on high ground, heading for Carbury.

Notwithstanding these known trackways, I believe we are missing one more. The modern road crosses the bog at its narrowest point, but the builders of an early, prehistoric road or wooden trackway would not have had exact information about the geography of the bog and therefore would have aimed at the island of Drumahon (around Spt 93, 757 329) for the most economical route to the high ground on the Carbury side. There is an existing short length of roadway around 770 323 which OS 1837 shows linked to 772 322. Some 400m of roadway, in line with this stretch, is still extant on the island. Extending our imaginary line across the bog, we meet high ground in Drehid near Spt 90, 733 348, then a spur of roadway at 728 352, and following it across the Kilcooney River another dead-end road at 722 359. I believe this to be the original route from which SMR 9/17 was later branched off.

Three known fossil toghers and one hypothetical one.

This proposed continuation from Drumahon to Spt 90, 733 348, passes through uncut bog. I chance to predict that a togher will be unearthed there in time.

I am told that the UCD Wetland Unit are coming to Kildare this summer, so we can perhaps expect more detailed results soon and, in due course, more accurate dating. But since one togher in the area has already been shown to date back to the Bronze Age, this is strong evidence that our Via Magna in valle – or parts of it – is/are of a similar ancient date. It also shows that the area around Timahoe was the ancient point of departure for travellers intending to cross the Midland Bogs.

Carbury

Our next target is Monasteroris. SMR 9/17 runs a considerable distance north of the modern bog road and its continuation would skirt Carbury Hill to the north while passing through the barony, whereas 18 and 19 would aim at a route bypassing it to the south. It is known that (the later barony of) Carbury originally belonged to Leinster but later (c. 500 ad) was taken over by and named after Cairpre, a scion of the Ui Néill of Tara, whose allegiances were with Meath rather than Leinster. This may have been a sound motive for re-routing the Via Magna onto a more southerly course. The northerly route would therefore appear to be the older one and is followed up here. (Accurate dating results will shed light on the validity – or otherwise – of this hypothesis.)

In the townland of Drehid there is a bridge called Art’s Bridge and, 400m to the north, New Bridge. Both bridges are of a similar modern date, built with ashlar blocks and concrete lintels. But Art’s Bridge must have had a predecessor of considerable age, old enough to give the townland its name. Townlands and (in many cases) their names go back to the 12th century, if not earlier.

Topography and field boundaries suggest that the roadway continued NW to Mylerstown Castle near Spt 122, 708 371, then more or less following the present road past Duffy’s Cross 667 380 to Williamstown. However, this route bypasses Carbury Hill which is the dominant height and with its prehistoric antiquities must have been an important site since the very early days. There must have been a connection, probably over the high ground at Newbury Demesne. From the foot of Carbury Hill a good high road runs WNW to Teelough cross road then NW to Williamstown.

At Williamstown the roadway crossed the Boyne River and its valley to the ruined castle and graveyard at Carrick 640 369 and from here it probably continued west to Grange Cross Roads 621 366 to Monasteroris 611 335. Alternatively, it may have followed the modern road (from Carrick) to Edenderry and from there to Monasteroris. Both routes necessitate passing through some unfavourable terrain.

The modern road from Carbury to Edenderry is another possibility, though topographically it is inferior to the northern routes.

Kilcock

What if the northern Via Magna passed through Kilcock? It is of interest to look for the old roadway from Kilcock to Cloncurry. The High Road, branching off from the modern N4 at 856 410, aiming for Cappagh Hill, 826 413, was the old stage coach road, but I would contend that an older road existed. It ran along the south side of the former race course (Commons West), providing a link between the town and the Ballycahan road at 871 393. It followed the latter to the sharp left turn at 856 393, continuing straight, where the Discovery map still shows a trackway at 848 397. A connection to Grange Hill, Spt 145, 401 836, marked by the proximity of a standing stone, is obvious. Here the roadway linked with the ancient roadway from Naas via Clane and Cloncurry into Meath. For a short distance of some 300m the modern road points directly at Cloncurry Cross, suggesting the ancient route. This is supported by the fact that this sight line passes through the site of the medieval town of Cloncurry.

I had earlier made a case for an important ancient route linking Naas with Tara. Based largely on topographic and cartographic evidence, as well as legend, Roger Horgan and I traced a roadway from Naas to Johnstown along the esker ridge to Bodenstown, through Blackhall estate, across the Liffey to Clane, on the esker to Boherhole, then along the modern road to Mount Armstrong and Donadea. The weakest part of that hypothetical roadway, the stretch from Clane to Mount Armstrong, has recently been validated. The hypothetical henge site at Boherhole Cross described by us has been examined by a team of archaeologists and confirmed as a definite monument, though its dating and exact nature are still uncertain. I now believe that that was indeed the ancient roadway, but that the first manmade road from Clane to Donadea / Dunmurraghill went via Kilmurry. From Donadea the road went by Ballagh, Hortland, Ovidstown, Grange Hill to Cloncurry and further on into Meath.

Conclusions

The exact course of the Slighe Mór, alias Via Magna, is not known, though it is generally understood to have run from Dublin to Galway roughly along the N4 / N6 road system. Medieval sources suggest two alternative routes, perhaps made necessary by political rivalry in early Christian times. Within the present framework, a route from Howth to the Dublin Ford (Ath Cliath) – Stoneybatter – Castleknock – Luttrellstown – Carton – Kilcock is suggested, with two alternatives from there: staying north of the Ryewater heading for Clonard via Rathcore, or crossing south to the Ballycahan Road – Cloncurry – Clonard.

A southern Route is followed up from Dublin (High Street) to Lucan – Celbridge – Taghadoe – Clonshanbo – Donadea – Dunmurraghill – Staplestown to Timahoe, with several alternatives through the bog to Monasteroris (Edenderry) in accordance with several identified (and one hypothesised) fossilised toghers. Because of the St Mochua connection, the route from Dublin to Celbridge is traced via Clondalkin. The importance of Timahoe as a jumping-off point for travel across the bog is recognised.

Links between the two routes would have existed at Dublin, Leixlip and Cloncurry.

The locations of the fords across the Liffey in Dublin, Celbridge and Leixlip are discussed. The present attempt to give the exact location of the Dublin ford should be of considerable interest.

In more general terms I have arrived at the conclusion that the original, natural Esker Riada roadways do not necessarily coincide with the first manmade Slighe Mór roads. With reference to the first sixty or so kilometres inland from Dublin, the topography in Meath suggests the more favourable natural route, whereas the roads linking all the monasteries and ecclesiastical sites in Leinster may represent the first major constructed road in the area. But then there are the ancient toghers at Timahoe.

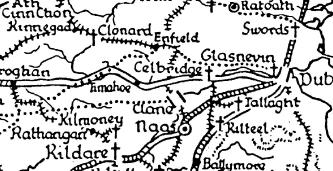

Detail from O’Loughlainn’s map of Roadways in Ancient Ireland (see Footnote No.6)

I like to thank Mario Corrigan, Ted Craven, Seamus Cullen, Tony Doohan, Michael Jacob and Michael Kavanagh for their assistance.

Hortland

Des O Leary

Ballysculloge, the original name for this area in North Kildare, was later anglicised to Scullogestown. In 1745 it was acquired by Revd Josiah Hort and renamed Hortland, a name still in use to the present day.

Ballysculloge ('town of the small farmer') rises from the bog of Allen in the south to the higher, more arable lands in the north-east. In medieval times it was one of four parishes which formed the barony of Oughterany, the other three being Cloncurry, Donadea and Dunmurraghill. It is clear from the evidence that the area was inhabited from the earliest times. In 1958 a stone axe-head was found in a field bank in Hortland. In the same townland are the remains of an old Celtic rath, and in 1973 a crannog, which could date from early Christian times, was discovered at the back entrance to Knockanally.

Shortly after the Norman invasion in 1169 most of the North Kildare area became the property of Adam de Hereford. In order to protect their lands and possessions from the unconquered Irish to the west of Ballysculloge, the de Herefords constructed the earthen motte, in the townland basically the same as it stands today, although the wooden castle on top has long since disappeared.

The next landlords associated with Ballysculloge are the de Flatesburys. In 1286 Robert de Flatesbury was seneschal of the county palatine of Kildare and in 1288 lord of the manor of Ballymascoloch in Co. Kildare. In 1305 Robert’s son, Symon, sued the Abbey of St Thomas for the advowson of Ballymascoloch, i.e. the right to appoint a clergyman.

Symon's son, Robert, was appointed collector of the King’s Revenue in the barony of Offelan, and held the manor of Ballymasculloch at the date of his death in 1367. Robert’s son Patrick became sheriff of Kildare in 1394 and in 1425 was still in possession of Ballymasculloch. Patrick’s eldest son, James, married Eleanor Wogan of Rathcoffey; they had two daughters. The eldest daughter, Margaret, married John Fitzjohn Fitzgerald who became proprietor of Ballysculloge. In 1442 one John Duff sold his holdings in the area to the Fitzgeralds, including parcels of land in Le Camagh, Ardkepagh, Gurtin, Baghall, Gurtindoon and Lana, all townlands within the parish of Ballysculloge.

The most famous member of the Flatesbury family was Philip Flatesbury of Johnstown who is credited with writing The Earl of Kildare's Red Book, a section of which has been translated by Mr Tadgh Hayden, and is available in Newbridge library.

In 1588, over 100 years after the Fitzgeralds had first acquired parts of Ballysculloge, Thomas, earl of Ormonde, made a grant of the Barony of Oughterany, sometimes known as the Cloncurry grant, to Richard Aylmer of Lyons. This grant did not include the parish of Ballysculloge. In the Civil Survey of 1654 the area is referred to as Skulloghstown and the proprietor given as Maurice Fitzgerald of Osberstown, with a reference as follows:

The town and parish of Skulloghstown afore said lyeth Eastward of the river called Blackwater Westward of George Aylmer of Hartwell his lands at Fenaghes, Northward of Sir Andrew Aylmer his lands at Donadea and Southward of the said Sir Andrew Aylmer his lands of Ovedstown. There is upon ye aforesaid lands at Skullogstowne one stone house which is valued to be worth twenty pounds. There is also upon the said lands one quarry of stone.

The stone house identified above may be what O’Keeffe referred to in the Ordnance Survey Letters as an ‘old castle beside the moat [motte]’, which formerly belonged to the Fitzgeralds. The civil survey makes no reference to any other townland in the parish. It says, ‘The great and small tithes were in the year 1640 possessed by Christopher Golborne Clerke.’ According to an old land lease the original village of Scullogstown was located along the old road adjacant to the pond. Fairs were held in the village on 2 May and 9 December.

There is no reference to any church or any association with an early Christian saint connected with the area prior to the Norman invasion. The first reference to a church in Scullogstown was a transaction early in the thirteenth century, when the church was given by Roger de Hereford to St Thomas Abbey, Dublin. In 1336 a Clergyman named William was described as vicar of Ballysculloge. The paternal feast of the parish of Scullogstown is the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin. In the early 1700s William Balfe is described as being Parish Priest of Scullogstown, he was ordained in 1698 in Cork by Dr John Sleyne, Bishop of Cork; sureties were Simon MacEvey of Graigesallagh, and Peter Walsh of Donecomfort, farmer.

Thomas Boyle, Vicar of Kilcock, reported to the Protestant Archbishop in 1731:

Ballyscullogue had no Chapel or Masshouse, nunnery or Friary, but public mass is said on Sundays by Andrew Egen at the house of Mr John Fitzgerald in Ballynafah.

There is within the confines of the graveyard the octagonal head of an ancient limestone font. One of the earliest recorded burials was that of Bryan McDonal who died in 1745.

In the established church of Ireland register of 1807 Scullogstown is described as being part of the Benefice of Kilcock Cloncurry and Ballinafagh, but there was no reference to a church in Scullogstown. It is likely that the church was in decline from the reformation period.

In 1666 Edward Sutton leased the town and lands of Scullogstown from Maurice Fitzgerald for 41 years. Over the next number of years the lease of lands at Scullogstown changed hands on numerous occasions while remaining in the ownership of the Fitzgeralds. In 1710 a George Brehold sub-let 700 acres (284ha) to Charles Armstrong of Mountarmstrong, Donadea.

When dealing with old land documents and leases it is not always clear if the title referred to is that of overlordship, or of a subordinate degree.

Reference is made in 1715 to other townlands in the parish when the said Charles Armstrong purchased the lands of Newtown-Monyluggagh, Ballyteigh, Achacka, LinnKeile. In 1723 the Fitzgeralds sold the lands of Knockanally to Joseph Leeson, later earl of Milltown.

In 1742 James Fitzgerald let part of the hill of Scullogstown as well as Foxes holdings and two parks behind James Magavins house to Charles Fitzgerald of Clonshambo. This agreement was witnessed by a Denis Kanavan, and contained 120 acres. Two years later James Fitzgerald let 35 acres to a Robert Daly of Dublin; also included was the house and gardens lately held by Patrick Gernon and Marks Dooney.

In 1745 the Fitzgeralds seemed to have redeemed the remaining leases of Scullogstown. They sold the manor, containing 868 acres, including a watermill to the Revd Josiah Hort, Bishop of Tuam, for the sum of £5,373. Horts purchase did not include the townlands of Knockanally (seat of the Coats family for some time) Ballyteige, Achachy, Lennkeill or Newtownmoneenluggagh. The Fitzgeralds continued to lease the lands of Scullogstown until 1766.

Joshiah Hort was born near Bath in England in 1673 he was educated at Clare College Cambridge, where he graduated. He was ordained bishop of Norwich and became chaplain to Mr Hampden M.P. for Bucks. In 1709 he became chaplain to Earl Wharton the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. After his arrival in Ireland he obtained a parish, and after holding two deaneries (Ferns and Leighlin) and two bishoprics, (Kilmore and Ardagh) he became eventually Archbishop of Tuam in 1742.

Although he only owned Scullogstown for a short period prior to his death he certainly created an impression in the area. Firstly he changed the name of the area to Hortland. He erected a mansion on his lands in 1748 designed by Richard Castle. In the same year he constructed a windmill on which the following inscription was inserted ‘This mill was erected by his grace Josh Hort, Archbishop of Tuam 1748’. The outline of this mill is still visible. Hort constructed a new stone bridge across the Blackwater known as the Bishops chair with the inscription ‘This bridge was built by Josiah Hort Lord Arch Bishop of Tuam one of his Majesties most honorable privy Councilors in ye year 1745.’

Josiah Hort married Elizabeth Fitzmaurice of Gallane Co. Kerry in1725. Its unlikely that Hort or his wife ever lived in the new Mansion, as can be seen from an agreement made in 1750 whereby Hort let the Mansion previously held by Patrick Luby to a Mr Colligan. Hort renewed the lease agreement with Charles Fitzgerald of Clonshambo except for 38 acres, which was let to Laurence Downey.

Archbishop Hort died in 1751 and was buried in the churchyard of St Georges Dublin, where there is a monument to his memory. In his will Hort identified his estates as Moyvalley Clonduff, Ballinderry, Ballydrummy, and Hortland; this seems an extraordinary accumulation of land in such a short space of time. All his property was left in trust for his second son John.

Archbishop Hort was succeeded at Hortland by his eldest son Josiah George, (who later became a clergyman.) He married Jane Marie Hawkes in 1766,in the same year Revd J G Hort leased Hortland to Thomas Eyre.

Revd J.G. Hort died in 1786 and was succeeded in Hortland by his brother John. In 1767 John was appointed Consul-General of Lisbon and was at the same time given a baronetcy. He married Margaret Aylmer, daughter of Sir Fitzgerald Aylmer of Donadea. After the 1798 rebellion Sir John Hort Bart lodged a claim for compensation for £950 - 12- 9 for damages to Hortland House caused by United Irishmen prior to the Battle of Ovidstown. He died at Brighton on October 23rd 1807 and is buried at St. George’s, London.

It is unlikely that Sir John Hort and his wife ever resided at Hortland and it seems that his son Sir Josiah William 2nd Baronet was the first of the family to live in the mansion. He held the office of High Sheriff of Kildare in 1818, and represented the County in parliament from 1831 to 1832.

Sir Josiah William married Louisa Georgina Caldwell from County Fermanagh in 1823. As part of the marriage settlement; it was agreed that ‘Sir John Caldwell would within Six months after the solemnization of the said marriage pay to Sir Josiah William Hort the sum of £5,000 also payment of a further £8,000 pounds after the death of Sir John Caldwell.’

It was during Sir Josiah Williams’s time at Hortland that the various changes took place. Those included the re-alignment of the existing road away from his residence. Some traces of the old road are visible still from Leonard’s avenue across the hill to a position a short distance to the east of Knockanally gates. Sir Josiah William Hort was responsible for moving some of his tenants and workmen from the vicinity of his house to newly constructed stone houses on the west side of the Blackwater. This settlement was commonly known as The Street of Hortland, He also constructed a lime kiln adjacent to an existing quarry.

In 1823 parliament passed an act, which stated that tithes due to the established church should be paid in money and not crops as was previously the case. Commissioners were appointed for each parish to access the tithe payment due from the landholder. The commissioner appointed for the parish of Scullogstown was Joseph Wybrant, who carried out the survey in 1833 and recorded the information in The Tithe applotment books.

Fifty-one farmers were assessed as being eligible for the payment of tithes. The assessment was based on 543 acres with the majority of holdings measuring from 2 to 10 acres. Sir William Horts liability was calculated on 137 acres and amounted to £4 -10-00. The combined tithes for the parish amounted to £58 –18-11. Wybrant included three other townlands in his survey of the parish; Knockanally, Ballyteigue and de Cathea Newtown or Scarletstown. It is probable that Scarletstown was the original name of the present town land of Newtownmoneenluggagh as Walter Fitzgerald referred to a Scarletstown in connection with The Flatesbury Family in Trustees maps of 1688-1702.

In 1837 Lewis describes Hortland parish as containing 539 inhabitants and the seat of Sir Josiah William Hort. It is a vicarage in the diocese of Kildare forming part of the union of Kilcock. The rectory is impropriate in Lord Cloncurry. In the RC divisions it forms part of the union or district of Kilcock.

In the same year the Ordnance Survey Office produced the first accurate maps of the county on a scale 6" to a mile. Those maps defined the town land boundaries and the exact acreage.

The Irish Poor law act of 1838 made it necessary that all land and buildings should be valued, so that a rate of so much per pound could be levied to finance the relief of the poor. Richard Griffith was commissioned to provide a general valuation of rateable property in Ireland. This work was completed in the 1850s, and was commonly known as ‘Griffiths Valuation’. Sir William Hort second Baronet held the town lands of Hortland and Ballyteige totaling 1571 acres. There were 43 holdings leased from the estate and Hort himself held almost 700 acres, mostly bogland.

In the census of Ireland, 1841, the population of Hortland was 453, with 58 families someway involved in Agriculture. By 1851 the population was 366 a decrease of 19%. This decrease is similar to the national average and was due principally to the affects of the famine.

To alleviate the suffering and poverty of this period some landowners iniated famine relief works; and in 1847 Sir Josiah William Hort was granted £800 from the Commissioner of Public Works for improved drainage in Hortland and Ballyteige. In the same year he contributed £15 to the Donadea Poor Relief Committee. In 1848 Lady Louisa Hort wrote to the Society of Friends requesting aid for what she described as the ‘truly destitute and most depressing poor people by whom we are immediately surrounded’.

Shortly before Sir Josiah William Hort died in 1870 he had moved residence from Hortland House to No. 1 Merrion Square East, Dublin. Hortland house was let to J.H. Peart, Esq. After Sir Josiah Williams death the Hortland estates passed to his first son, Sir John Josiah Hort, third Bart.

Sir John was Lieutenant General in the army and served through the Crimean wars. He died unmarried in 1882 and the estates passed to his brother, Sir William Fitzmaurice Josiah Hort, forth baronet, and Barrister at Law.

Sir William married firstly Harriet Stevenson in 1866, secondly Catherine Anne Villiers. Sir William and Catherine lived at Canicas Cottage, Co. Kilkenny. He died without issue in 1887. The estates then passed to his brother, Sir Fenton Josiah Hort, fifth baronet. Sir Fenton was Lieutenant Colonel, 3rd Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusealers. He died without issue in 1902 and the baronetcy passed to his first cousin Sir Arthur Fenton, sixth baronet of Hortland.

The mansion designed by Richard Castle was at the turn of the century described as being in a dilapidated condition.

From 1869 the ownership of land was transferred gradually from the landlords to the tenant farmers. This process was carried out through a serious of land purchase acts. The last land act administered by the British government occurred in 1909. It was this act that divided the Hortland estate amongst the tenantery. The principal recipient was Herbert Warren, who received 162 acres.

Sir Arthur Fenton Hort, 6th baronet, was the last member of the dynasty to hold the Hortland Estates.

The Baltracey Quakers

Seamus Cullen

The Society of Friends or Quakers, as they were more widely known, became established in Ireland from the late 1600s. Following the wars of the 1640s there was a shortage of merchant class citizens in the country, and this void was filled by planters and emigrants from England. Many of these people joined the Society of Friends, and within a short time Quaker families spread throughout the country.

Quaker communities sprang up in the northern half of Kildare with Meeting Houses at Edenderry, Rathangan, Baltyboys (near Blessington) and Timahoe. These rural Quakers were mainly engaged in farming, milling and brewing as well as small merchant businesses.

Prominent among the Edenderry Quakers was a branch of the Watson family, who originally moved from Cumberland to Carlow in the pre-1640 period. Samuel Watson (1659-1732) prospered in Edenderry and leased land in the immediate neighbourhood. One estate was at Ballinamullagh, Carbury, which he acquired in 1715. It had an area of 462 acres (185 hectares), and the lease was for the lives of two of his sons, William and Benjamin. Benjamin died shortly after and William subsequently took over the management of the farm. This William married his (unrelated) namesake Mary Watson from Derrygarron, Rathangan, in 1720. Mary was the daughter of a Colonel Tom Watson who served in King William’s campaigns in Ireland in the 1690s.

A letter in the Watson family possession, dating from 1853, gives an account of this Colonel Watson as follows:

Colonel Watson came over to Ireland with King William […]. Though pressed by the King to accept of an estate refused it and purchased the interest of land from the natives and settled at Derrygarron (in English a horse grove) it was mostly in wood of oak. Colonel Watson was […] cousin to the late Marquess of Rockingham. After the battles were over he was disgusted with wars and joined our Society [the Quakers].

William and Mary had two daughters and a son, William (II). However, William (I) seems to have contracted an illness and died in 1729, aged 31. His will has survived and in it he left his estate to his son, with provision for his wife and daughters.

Also prominent among the Edenderry Quakers at that time were the Eves family. They originally came to Ireland from Leicestershire in 1660 and settled in County Wicklow. Two Eves brothers, Joseph and John, moved to Edenderry in the 1715 period and became successful businessmen. Another brother, Caleb, later followed them and in 1731 married William Watson’s widow Mary. Caleb then moved into the Watson house at Ballinamullagh and managed the farm. The next year a son, Mark, was born to the couple.

In 1734 Caleb purchased Baltracey Townland from a Dublin Baronet named Sir William Fownes. This townland is situated six kilometres south of Kilcock and has an area of 707 acres (283 ha), all arable land. Fownes had acquired Baltracey in 1707 from the previous owner Margaret Eustace. She was the widow of a prominent Jacobite officer, Sir Maurice Eustace from Castlemartin, Kilcullen, whose family had held the Townland from the medieval period. Fownes made many improvements to the estate, laying out orchards and plantations, building dwelling houses and possibly the original Baltracey House, a stone-walled slated farmhouse situated a quarter of a mile (400m) north-east of Baltracey Cross on an old road system. Beside this house was a farmyard consisting of barns, stables and a pigeon house. (Fat pigeons made up part of the payment which the Eves were required to pay Fownes for some years afterwards.) In about 1730 Fownes built a new corn-mill on the Baltracey River. This mill was probably built on or close to the site of a previous mill mentioned in the Civil Survey of 1654 and would have been one of the main attractions of this estate to the Quakers.

The Eves-Watsons moved to Baltracey, successfully managed the estate and operated the corn-mill. They were not isolated from fellow Quakers, as Timahoe was only five miles away and two families there were related to them. William Watson’s two paternal aunts, Sarah and Ruth Watson, were married to Henry Russell from Hodgestown and Robert Wyley from Gilltown, respectively. Timahoe was also their spiritual centre as they attended meetings in the Meeting House on a regular basis. In 1744 Elizabeth Watson, eldest daughter of Mary Eves, married Joseph Toplinson from Edenderry, and the next year her sister Mary married Isaac Haughton from Castlebibbon. Both weddings took place at the Meeting House in Timahoe. In 1747 their brother William Watson married his stepfather’s niece, Margaret Evens from County Wicklow. However, this marriage was not in accordance with their religion as the couple were married by a priest and as a result lost their membership of the Quaker religion. The couple lived in Baltracey with William working as a successful proprietor of the mill. His mother, Mary Eves, died in 1757 and was buried in Edenderry. Tragedy struck the tiny communities later that year when Mary and Caleb’s son Mark, who was heir to the estate, died at the age of twenty-three. With Caleb’s death in 1762 ownership of his estate passed to a relative, also named Mark Eves, from Co. Wicklow. It appears that William Watson, Caleb’s stepson, retained certain rights to the Estate but was not considered as the heir.

The Eves and Watsons continued to run the estate together. William Watson and his wife, Margaret, had nine children between 1748 and 1771. The community was not without it’s scandal when in 1775 Mary Watson, the eldest of the family, was expelled from the Quaker religion because she had dishonoured the community. The following is an account of this affair from that year:

Whereas Mary Watson, Daughter of William Watson of Baltracey, near Timahoe, was Educated in Profession of us the people called Quakers and did some time frequent Our Religious meeting but for want of taking heed to the Spirit of Truth in her heart which would have preserved her, Did join with the Temptation of the Enemy of her happiness so as to cohabit with a man in A criminal manner by whom she has had a child. Wherefore in order to clear the Truth we profess from the Reproach Occasioned by her Disorderly and Wicked Actions and for a Causion [sic] to Others We are concerned thus publicly to Testify against her and Deny her to be of Our Society nevertheless We Sincerely Desire that she may come to a true Sight and Sense of her misconduct and Witness that Godly Sorrow which Worketh True Repentance and thereby Find mercy with the Almighty.

After this incident the Watsons seem to have discontinued to practice their religion. Samuel, the second eldest son, was the first of this generation to get married in 1784 when he married his second cousin, Margaret Russell, from Hodgestown, Timahoe. Mark Eves that year leased Balfeighin Estate which is situated one kilometre north of Kilcock, and Samuel and his wife Margaret went to live there in the original Balfeighin House which dates from that time. In 1788 Thomas, William’s eldest son, leased land at Pheopstown from the Prentice family. This estate, situated just over three kilometres north of Balfeighin, is known as Larchill and is adorned with follies and artificial lakes. The follies pre-date the Watson ownership, but Larchill House dates from this time and was most likely built by the Watsons. Two years later, in 1790, Mark Eves let the area of Baltracey known as The Mill Land to William Watson’s daughters, Nancy and Sarah. The present Baltracey House is situated in this area of land and the oldest part of the building was built at that time by the Watsons. The two youngest Watson sons, Mark and William (III), had moved to Dublin and set up businesses. Mark subsequently leased Larchill for some years from his brother, Thomas.

William, having successfully served his apprenticeship as a haberdasher and tape manufacturer, went into business and opened a shop named The Spinning Wheel at No.30, New Row, Thomas Street, and he re-joined the Quakers in 1793 and married Margaret Wright from Co. Wexford. The couple then lived over the shop until William died at the early age of 29 in 1801, leaving three daughters under six and a fourth born later that year.

Mark Eves let the remainder of the Townland, known as Baltracey Farm, to Peter Doyle, a grazier by occupation and a member of the Quaker Community from Carlow in 1792. Included in the area of land was the original Baltracey House, outhouses, barns, stables, pigeon house and also orchards and gardens. A marriage was arranged between William’s daughter, Margaret, and Peter Doyle, and the couple took up residence in Baltracey, though it is not clear in which house. Mark Eves had also obtained the lease of Raheen Old, a neighbouring Townland, in 1794, from Revd Richard Cane, Rector of Larabryan, Maynooth, and two years later made an agreement with Robert ("Robin") Aylmer of Painstown which would result in the lands reverting to the latter at Mark’s death.

In 1793 the tiny community was shocked by the death in child birth of Margaret Doyle. The couple had been married for less than a year. Margaret’s baby, a daughter, survived and was named Margo.

The trying years of the late 1790s did not pass untroubled for the community. In 1796, when there was considerable Defender activity in the general area, the house of Mark Eves at Baltracey was attacked, which resulted in some damage to his property. It appears that during the attack Mark threatened to shoot at his attackers (he "fired a gun threat"). This was contrary to the laws of his religion, and a committee of Quakers was appointed in March of that year to investigate the matter. In the following August the committee also reported that Peter Doyle of Baltracey and Alexander Wiley of Timahoe kept firearms for the defence of their persons and property, and furthermore, that they had expressed their intentions to use them if necessary. This was not in accordance with the Quaker religion, and both men were expelled.

The following month, Mark Eves, who was in the process of making a claim for damages caused during the robbery of his home earlier in the year, was visited by at least one elder of his religion. Proceeding with the compensation claim was not regarded as proper by the Quakers. The inconsistency of his application was pointed out to him, and he appeared to see it was improper. He then expressed regret at not having consulted with his fellow Quakers on the matter, and from this it appears that he dropped his claim.

Mark Eves passed away in 1800, and under the terms of his will transferred the freehold of the Baltracey estate to his cousins, the Eves brothers William, Joshua and Samuel, from Edenderry. Mark’s lease of Balfeighin was subsequently acquired by it’s occupant, Samuel Watson. Samuel’s wife, Margaret, died the same year and was buried in Timahoe. They had two children, Samuel E. (Eves) and Anna. Their father remarried in 1805 to a widow from Kilcock named Ellen Kelly.

Peter Doyle died in 1805. His daughter, Margo, then aged 12, inherited the lease of Baltracey farm and it is likely that she was brought up by her relatives, the Watsons. (Her grandmother, Margaret Watson, was then still alive. Her husband, William Watson (II), had died in 1798.)

A marriage was arranged in 1811 between Margo Doyle, then aged 18, and Samuel E. Watson, her first cousin. Their marriage arrangement would unite the three estates then in the family’s possession. Thomas Watson, the senior member of the family, and his brother Mark transferred Larchill to their nephew, Samuel E., and the house there became the residence of the newlyweds. Samuel senior transferred the lease of Balfeighin to his son, Samuel E., while Margo Doyle brought to the marriage the lease of the greater part of Baltracey.

In 1820, Samuel E. Watson inherited half the estate of his uncle, Samuel Russell, in Hodgestown, Timahoe. This brought together four estates with a total area of 1,627 acres (650ha). Thomas Watson died in Baltracey House in 1822, and with the death of his sister, Nancy, four years later, finally brought to an end over ninety years of residence by the Quaker families in the Townland.

In 1828 the corn-mill was let by James Webb, a nephew of the Watsons, to Samuel Walsh who had earlier moved into Baltracey House, together with his family. Margo Doyle Watson died childless in 1820 and her husband, Samuel E., died in 1836 at Larchill. They were both buried in the Quaker cemetery at Timahoe. Samuel E. had one sister, Anna, who had married Richard Neale, from Coolrane Mill, Mountrath. Anna’s eldest son, Samuel Neale, became the heir to the Watson estates, but he had to fulfil one important stipulation, laid down by his uncle’s will, in order to inherit the property. This required him to change his surname to Watson, and failing to comply with this stipulation, the estates would then be offered to his younger brothers, with the same arrangement. Samuel complied with his uncle’s wishes and changed his name by deed-poll and thus inherited the Watson estates. Samuel Neale Watson, as he was now known, married Susanna Davis in 1840 and lived mainly in Dublin.

The freehold ownership of Baltracey townland passed to Elizabeth, wife of Samuel Eves of Edenderry, at this time. Following Elizabeth’s death in 1854, the estate passed to her two unmarried daughters, Sarah and Jane. Her only son, Thomas, was disowned and disinherited for marrying outside the Quaker religion. In 1854, Sarah and Jane re-let the mill and the Mill Land at Baltracey to their tenant, Samuel Walsh. Two years later, they also re-let the former Doyle estate to Samuel Neale Watson. With the passing of the Land Acts of the 1880s, the Eves and the Watsons lost considerable control of their estates to the tenants, finally losing the freehold following the Land Act of 1903.

Samuel Neale Watson died in 1883. His heir, Samuel Henry, kept up the family tradition in milling when he married Margaret Goodbody, a member of that prominent milling family, the Goodbodys of Clara. Samuel Henry’s son, Cecil, was a well known Dublin Quaker and pacifist all his life. He founded the Court Laundry in 1906 and was a model employer. In 1920 he added the name Neill to his surname, in recognition of his grandfather’s family, changing the family name to Neill-Watson.

Only one local tradition of the Quaker families in Baltracey survives. A raised area in a field close to the original Baltracey House has been traditionally referred to as ‘Quaker burial ground’. This area has not been enclosed since at least 1837, and no record of Quaker burials in the locality exists. It is likely to have been a children’s burial ground and may have been used by the Quaker community to inter stillborn babies.

Today, over two-and-a-half centuries later, three surviving buildings, Larchill House, the present Baltracey House and the original but now roofless Balfeighin House, remain as a reminder of this once prosperous Quaker family.